In a recent blog post I mentioned that I was creating three altered books for the exhibition, Bugs: Beauty and Danger. I wanted the third altered book to be a close up of an ivy-covered tree with moths, bees, wasps and other wildlife. I often draw ivy around trees as it’s ubiquitous in the woods and parks. I thought I’d start looking at it a bit more closely.

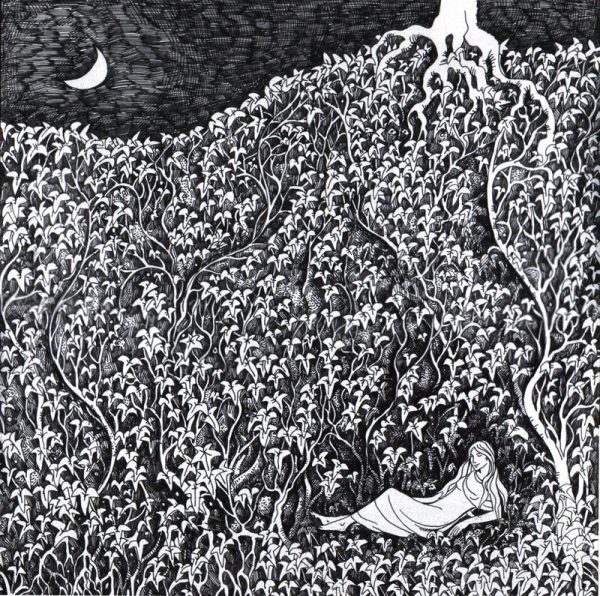

There is something dark about ivy and not just because it has dark, green leaves. It actively seeks out shade. It conceals secrets, covers long forgotten tombs, reclaims ruins silently.

Dark places like woodland floors and the feet of trees, crumbling walls and the damp Victorian corners of cottage gardens are its abode. There is something ancient about ivy, it carries a message from the past. It creeps over everything. I think of the cloven-hoofed god Pan. I think of ivy wreaths. I think of death and churchyards, tombs and the hands of ivy linking lovers beyond the grave.

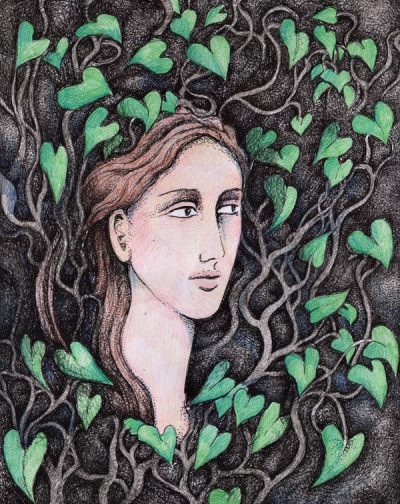

The Ancient Greek goddess of youth, Hebe, was associated with ivy, serving nectar and ambrosia to the Olympian gods and goddesses. There was even a secret festival called Kissotomoi or Ivycutters in the ancient Greek city of Philos. Ivy represented the grapevine and was a symbol of Dionysus, god of wine, festivity, wild pleasure and vegetation.

Ivy has long been a symbol of fidelity and marriage and was made into a wreath and given to newly wedded couples. The Ancient Celts made evergreen plants symbols of hope, rebirth, protection and good fortune and brought them into houses around the winter solstice. Ivy was adopted by early Christians along with holly as symbols of prosperity and charity. Both feature in Christmas carols, ivy representing the female aspect, holly the male.

English ivy, Hedera helix, has two stages with different leaf shapes. The vegetative stage has large, lobed leaves and is found in all sorts of places, climbing up trees and buildings. It is negatively phototrophic, which means it is drawn to shade because this often means there is a structure that it can climb. The reproductive stage of the plant has oval, pointed leaves. From this part of the plant come clusters of greenish-yellow flowers that attract insects including the Pink-barred Sallow, Angle Shades, Green-brindled Crescent, Yellow-line Quaker and Lunar Underwing. Beautiful names, beautiful moths. There is also a mining bee associated with ivy, the Ivy Bee, Colletes hederae. The flowers are followed by blue-black berries enjoyed by blackbirds, thrushes, jays and other birds.

Apparently, hederagenin, a substance found in ivy leaves, has been shown to kill various tumour cells.

I went on a short walk from my house picking ivy leaves wherever I came across them. There seem to be quite a diverse range of leaf shapes:

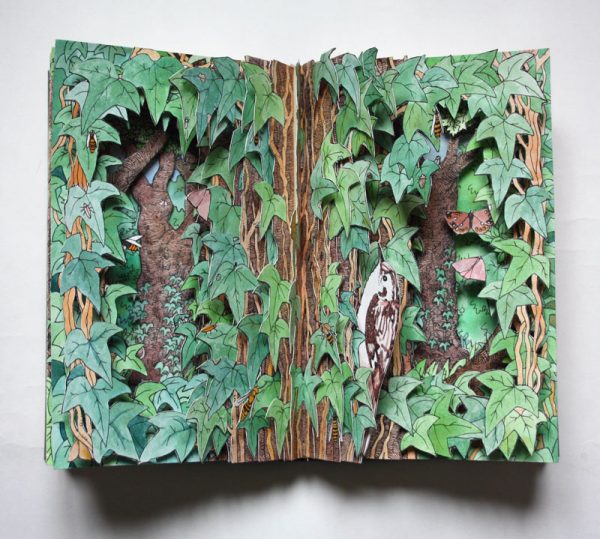

In my altered book I have included moths, bees, wasps , a bees nest, a speckled wood butterfly and a treecreeper. I love treescreepers, they often join mixed tit flocks at this time of year. They feed on small insects and forage in the bark of trees. I was fascinated to learn on Winterwatch recently that treecreepers roost in bark crevices if there is a tree with suitably soft bark.

Here is my Ivy Tree altered book ready to be sent to Groundwork Gallery for the exhibition:

One can use ivy in basketry work. Anyone in the Lewes area wishing to make ivy woven bags – check out Native Hands workshop in November.