Our weekend trip to Wiltshire began with a day of respite from the rain and strong winds. We drove to West Woods, southwest of Marlborough, for a walk along the Wansdyke path. The path runs parallel to an ancient dyke, originally named Woden’s Dyke from the Norse God Odin, god of wisdom. It was created in the early Medieval period to divide Celtic kingdoms or keep the Saxons away. It is about 21 miles long, but we only walked a small section of it through the beech wood, protected a little from the wind and accompanied by the croak of ravens.

Back in the car, we cheered ourselves up by singing Gentleman Dude by Julien Cope. Along with creating music, he wrote the Modern Antiquarian, a book about all sorts of prehistoric places in the UK. Not far from us was West Kennet Long Barrow, so we donned wellies and braved the winds and puddles to walk to the ancient site.

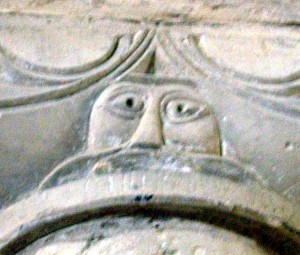

The long barrow is surprisingly – well, long. The entrance is sheltered by some giant sarsen stones and, behind these, I was pleased to discover that you can go right inside the tomb. The interior is a passageway of algal covered slabs leading to a larger chamber at the end. There are five side chambers off the main passageway.

It was dark and still inside, quite a contrast to the bleak windswept fields without. It reminded me of Gavrinis without the carvings. I had a good feeling about it and could imagine all the rituals, camps and festivities that have taken place over the centuries within those sacred, cave-like spaces.

The barrow has been dated to about 3,700 BCE, the start of early farming, the heyday of pastoralism before the ascendance of crop cultivation. Artifacts were found within the tomb(s) – pottery, flint tools, coins and other offerings – alongside skeletons of about 36 people.

Descending from the long barrow, we detoured along the back of a strip of woodland. There was no official path, but footprints in the soft soil betrayed the countless other people who had done the same.

We were in search of a not-so-secret spring, Swallowhead Springs. At the end of the wood, we slipped through a gap in the fence and there it was, a area of lush grass and clear-running water seeping out from a bank. A red kite hung suspended over the field behind, jittering, and manoeuvring in the windy gusts from the southwest.

Central to the spring area, is a willow tree whose boughs arch to the ground, a clootie tree. Tangled within its branches are ribbons and offerings – a mug, corn dollies, candles, a little plaque with two hares on it, coins embedded in its bark. Some speculate that it was considered holy in ancient times, a place belonging to Brigid, an early Irish goddess of dawn, spring, fertility and healing. True or not, the place has become sacred to neo-pagans today and important to spring seekers like us.

The spring helps feed the River Kennet that flows beside the willow. Sarsen stepping stones have been placed in the river to provide access from the field to the north. On the day of our visit the river was high, submerging the stepping stones, flowing cloudy green, the colour of fluorite. A fallen crack willow bridged the river; it too was decked with ribbons.

We lingered, peering into the clear spring water with its waving verdant weeds, enjoying the quiet beauty of this sheltered corner. Then we made our way back to the car and headed to Avebury.

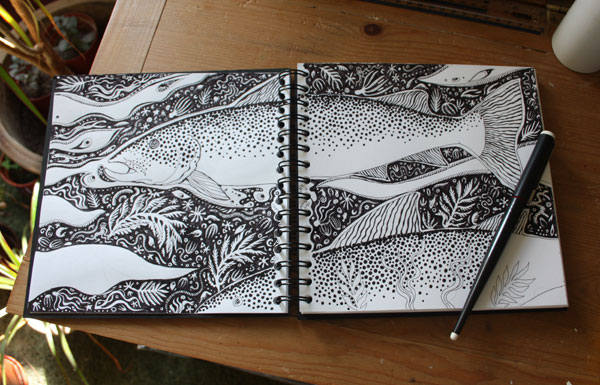

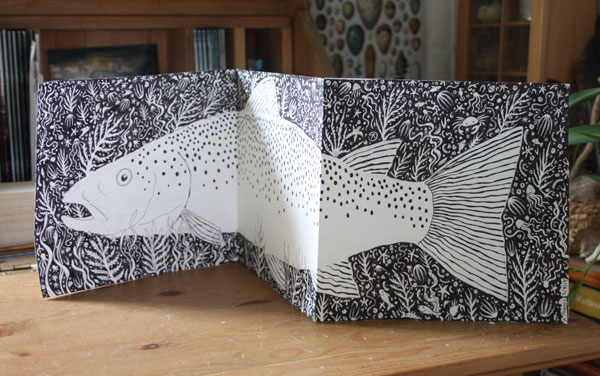

That night I had a dream. I was with a group of scientists learning about the difficulties they face in the world today with the climate emergency, bush fires, coronavirus, species extinctions, flooding, refugees etc. I was told that some scientists in remote places were forbidden to look out of the windows of their vehicles and had to watch virtual reality scenes instead, so bad was the devastation to the environment. Incongruously, among the scientists in the dream, was a willow grower lining up pots of willow trees. I was mesmerised by the apple green sunlight shining through the willow leaves. The light caught a gemstone, the sliver of a turquoise sea; it dazzled me. Then the willow grower handed me a book with well-loved pages saying I should read it as it was about willow trees. I remember musing about how good it would be to have answers to some of the world’s problems hidden within the willow tree. For a start, there is salicin from willow bark, a chemical similar to aspirin, but, perhaps there is more. Planting trees throughout the world is certainly part of the solution to some issues. Maybe the answers do lie with the trees – or with the birds as I have often thought. The croak of the raven…

I have always had a fondness for willow trees. In the garden of my childhood home, we had a weeping willow in which I used to sit. They are associated with water and the moon and I think there is a lovely flowing beauty about them. I know a little about willows, but now I shall endeavour to learn more.

We left Cherhill the following day just before storm Dennis came with full impact. After driving for an hour, the car decided to pack up and we became stranded on a roundabout. The winds grew and the rain lashed while we waited three hours for the RAC. Again, we cheered ourselves up singing Julian Cope songs and watching seagulls play in the rain.

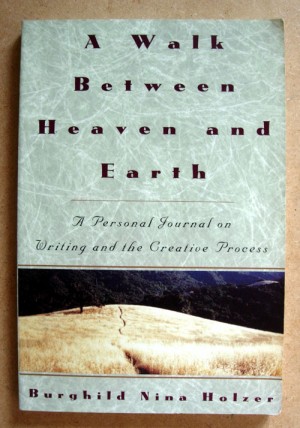

I have just finished reading “A Walk Between Heaven and Earth” by Burghild Nina Holzer. It is a lovely book about how to write a creative journal, written in the way of a journal. Burghild’s writing shines in its simplicity and beauty. There are many passages I like, such as the quote on the back of the book:

I have just finished reading “A Walk Between Heaven and Earth” by Burghild Nina Holzer. It is a lovely book about how to write a creative journal, written in the way of a journal. Burghild’s writing shines in its simplicity and beauty. There are many passages I like, such as the quote on the back of the book: