This piece was first published on the Caught by the River website in March 2018.

On a cold February afternoon I stand with my partner in a ruin of crenellated walls, towers within towers and a gatehouse open to the sky. We wander the rubble fragments of centuries past and sit with the age of stones. No longer the home of landed gentry, Norfolk Horn sheep, the rhythm of loom, Baconsthorpe Castle in Norfolk is a square of crumbled walls with a moat and mere surrounded by fields, copses and damp hollows. Flint, mortar brick, ivy and nettle. Bones. Rooks and crows caw and congregate in its leafless trees. Against the fading light the gatehouse throws a solemn shadow over the grounds, a mist of teasel and dead fireweed all around.

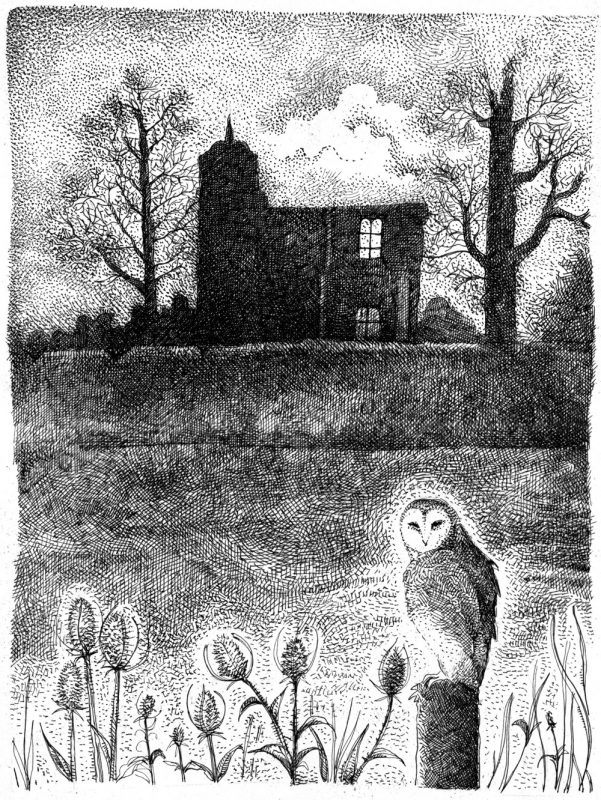

Like a mirage on the eastern boundary of the ruins, the white shape of a barn owl appears. It’s dusk, a changing hour; barn owl time. The bird seems almost a figment of my imagination, moon powder white in the pastel landscape. It flies with such softness, each feather barbed to make no sound, to hold the air, fluid and weightless like a breath over the land. Perhaps it is companion to the phantom that haunts these ruins, the one who wanders the moat and betrays his presence by dropping stones that ripple the reflected sky of the waters. With its banshee screech echoing through the nocturnal hours it is not surprising that the barn owl was seen as a harbinger of death in earlier times.

The barn owl alights on a short wooden post – a white, twilight flame. Its head turns, listening; an alert attentive bird. It ruffles its feathers and I see clearly through binoculars its heart moon face, its understated beak, its dappled breast feathers.

I once found a dead barn owl. It lay between the cabins on Havergate Island off the Suffolk coast, a mass of sodden feathers on a hollow-eyed carcass. I felt a strong sense of loss for this fallen, lunar bird now leached of life. It must have succumbed to the harsh winter, a lack of food or the poison put down to keep the rats at bay. The out-building where it roosted was empty, with rounded, dark pellets strewn about the floor.

More recently I found a feather that looked like it belonged to a barn owl. Small, soft, fawn and teardrop-tipped, it lay in long grass beneath a ruminating autumn sky in the shadow of the South Downs, providing evidence of their presence there. I returned again and again to the site at dusk, but the owl proved elusive and I began to doubt myself. I began to search more widely. Look for rough, unimproved grasslands, look for farms with barns away from roads and be hopeful, I told myself.

I remember reading that barn owls need undisturbed places to breed – old barns are favoured but other buildings, tree hollows or cliffs holes will sometimes do. In some parts of their range, a lack of suitable nesting sites reduces their opportunity to breed. Elsewhere their habitat is in decline. They prefer to be away from roads in areas with rough grassland and a healthy vole population, although they will hunt and eat other small mammals, frogs and nestlings.

Now the owl lifts up off the post, flaps low along the edge beating the bounds. Perhaps it has a partner and potential nest site tucked away in a barn nearby. It may be winter and cold but it’s still and dry and voles will be active; the owl will probably not go hungry. We keep watch, hoping it will swoop down suddenly – talons out, head back – onto an unsuspecting prey. Silently. But it’s back on the post, waiting, its head cocked. It sits and listens, waits and listens, while we watch from a distance. With the evening encroaching it looks vulnerable in its solitude.

Now everything is amber. Between the flint walls in the fading light, there’s a new magic to the place. Shadows of the ruin elongate as the sun teeters on the tree-fringed horizon; it’s time for us to leave. We say goodbye to the ruins and the Baconsthorpe owl, wishing it success as it patrols its home among the stones beneath the enormous Norfolk skies.