Continuing the subterranean theme, on a recent trip to Gloucestershire I visited a couple of long barrows with my partner. Walking part of the Cotswolds Way we came upon Belas Knap Long Barrow, an elongated mound which can be seen from quite a long distance away. From the side it is triangular in shape, rucked up from the earth. We approached it on a path the colour of terracota.

Belas Knap – possibly meaning “Beautiful Hill” – is Neolithic, 5500 years old and is, indeed, a beautiful hill; marbled white butterflies flit amongst the field scabious and red clover flowers. It is a rounded, elongated mound – the earth’s pregnant belly – and has a “false” entrance and four cave-like side chambers where 38 human skeletons have been found entombed within this womb of earth. The small chambers, with neatly layered dry stone walls, make adequate shelter from the elements if one enters on hands and knees.

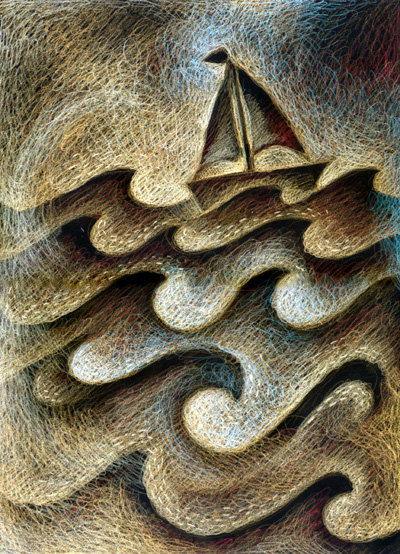

According to Robert John Langdon, the area was once a land of water and long lost rivers, and the long barrows may have been “Boats to the Afterlife”. It’s a beautiful, but controversial, idea. It was later, during the time of the Vikings in Anglo-Saxon Britain, that the dead were buried within real, wooden boats intended for the Afterlife – Ship Burials.

The other Neolithic long barrow we visited was Uley Long Barrow just off the Cotswold Way. It is also called Hetty Pegler’s Tump after the wife of the seventeenth century landowner where the long barrow is situated. This long barrow can be entered and its interior chambers explored.

Inside it was dark, musty, silent. The interior chambers were coal black so I set my camera to flash and took a photo; it was like entering a cave. Were the ancients trying to replicate caves in an otherwise cave-free landscape? I shouted into the void but my voice died on my lips, muffled and lost in the blackness. It felt close, slightly oppressive – I could almost feel the weight of rock and earth above. There was I within the womb of peace, the resting, liminal place of ancestors. Perhaps a place to commune with their spirits and acknowledge death. I pondered a moment and felt, ever-so-slightly, my materiality, my sense of self, dissolving into the velvet darkness about me.

Some long barrows have acoustic properties and I’m reminded of a programme on Radio 4 last year called Noise, A Human History by Professor David Hendy. In two episodes, he explored the acoustics of stone circles and caves. Sounds, or their absence, may have played an important role in making these sites sacred.

In some studies of Neolithic burial chambers, it has been found that during acoustic experiments, researchers experienced deep trance-like states and drumming vibrations were enhanced within the chambers.

“[West Kennet Long Barrow] was never just a tomb, it was a liminal crossing place, where shamans journeyed to ancestral realms for knowledge and healing”. Peter Knight